Update 5 June 2010: In less than a year, this article is already out of date. First, NASA’s STEREO satellites have been supplanted by SDO as the ultimate solar observatory, and it’s gorgeous high resolution images of the Sun currently dominate astronomy image galleries. Second, the Sun’s unusually long dormant period finally ended – there is now usually plenty for solar observers to see. And finally, I am no longer observing for ASSA‘s solar section – personal commitments have not left me with enough time and so I have to lose out on contributing to real science.

Open any astronomy book you like, and turn to the chapter on the Sun. You will see a hysterical warning message telling you that you should under no circumstances look directly at the Sun, and you should especially never look at the Sun through a telescope because you will go blind. There’s a good reason for this: They’re horribly worried that some idiot will try exactly that, and be permanently blinded.

What we don’t always remember is that the

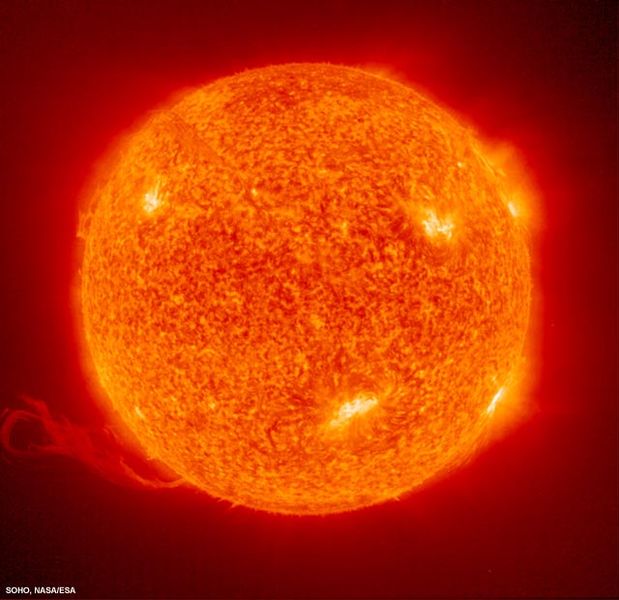

Sun is powered by a controlled thermonuclear reaction that makes the average H-bomb look like a firecracker. It consumes six hundred million tons of hydrogen per second, converting it into helium. It is so big that even at that rate, we expect it not to run out of fuel for another four or five billion years! It is very very hot, on the order of fifteen million degrees Celsius at the core, but only six thousand or so on the surface (or what passes for a surface – the Sun is not a solid body like earth, but composed of gas and plasma). By comparison, the surface sounds cool but it’s still hot enough to vaporise steel, titanium, even tungsten (if you’re not a metallurgist, tungsten has one of the highest melting points of any substance in the universe).

But the most important thing to realise about the Sun is that, being essentially a nuclear bomb, it produces radiation. Lots and lots of radiation. A large portion of this energy is in the form of electromagnetic radiation, from low frequency radio waves, to infra-red radiation (or Heat radiation), visible light, ultra-violet light, gamma rays, and so on. Hopefully it’s becoming clear why astronomers are so paranoid about people being stupid enough to focus all of that through a lens onto their own eye.

And yet… astronomers look at the Sun all the time. I personally am a member of the

Solar Section of

ASSA, and submit reports of daily observations (weather and schedule permitting). So how do we do it?

The safest and easiest way, and my personal choice, is to project an image onto a screen. It’s very simple, and you can do it yourself with a pair of binoculars and some office supplies. First, cut a hole into a large piece of cardboard (I use A4 but would prefer something bigger). The hole has to match the size of the largest lenses on your binoculars, because you’re going to poke one of them through that hole and hopefully have the cardboard mask stay in place by itself. Then you’ll need to set up a screen – I use a sheet of white paper on a clipboard, propped up against something. Then simply go outside, arrange the screen, and point the binoculars at the Sun. Be careful not to stand behind the binoculars – you might burn yourself. Once you get everything lined up properly, you’ll have a large bright and very shaky picture of the Sun shining on the screen. Once you’ve focused correctly, you will be able to see any large sunspots (although I wouldn’t be too hopeful this year – the Sun has been very quiet recently). If you have a telescope, you can use the same method, except that the tripod mounting will give you a far steadier image, and the greater magnification will reveal a lot more detail.

The professionals don’t bother with such things, though. They have elaborate filters placed on the telescope (at the LARGE end – anything inside the eyepiece, like those Sun filters provided with cheap telescopes, will become so hot that there’s a risk of them shattering and blinding you instantly) which only allow very specific colours to shine through, allowing them to take very detailed pictures of the churning ocean of gas which makes up the Sun’s surface. Such filters are also available for amateur astronomers.

But the very luckiest astronomers of all have access to a pair of dedicated Sun-worshiping

satellites, which are currently being manoeuvred into orbit around the Sun and which will maintain a 24 hour vigil, watching the Sun from two different angles and making sure that we record every single thing that the Sun does.

If you’re interested to keep an eye on what’s happening with the sun, you could always just head over to

http://www.spaceweather.com/ – they maintain an excellent archive of solar activity (amongst other things), as well as having up-to-date photographs of the sun highlighting any interesting activity. Just the thing for the armchair astronomer!