How do we know that the Earth is round?

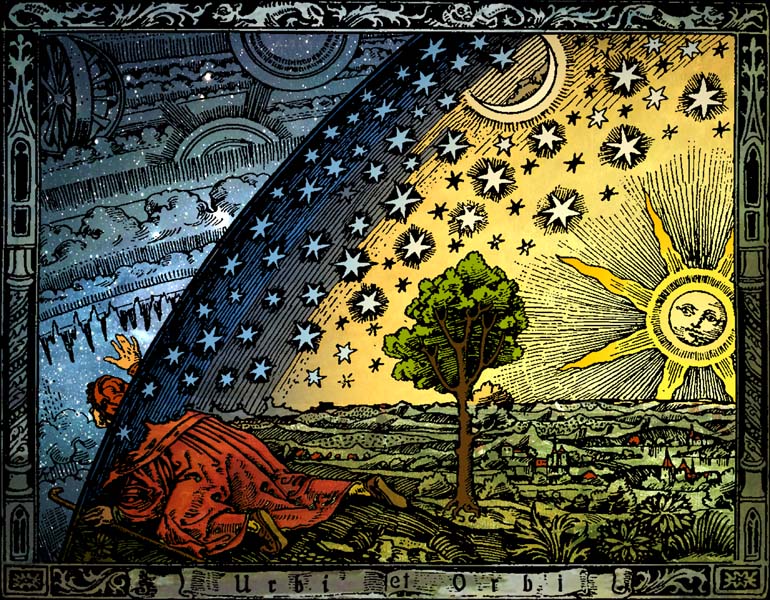

Most people would be surprised to learn that educated folk have known the true shape of the world since before the birth of Christ! But how? It all starts with Lunar Eclipses. To a thoughtful observer, it’s easy to work out what’s going on with a lunar eclipse. If you plot the paths of the Moon and the Sun through the sky, you’ll notice that whenever they’re at their furthest points from each other in the sky (About once a month), you get a full moon. From the shape of the phases of the moon, it’s pretty obvious that the Moon is round and that it’s being lit up by the Sun, and the different phases are directly connected to their relative positions. The Sun and the Moon each travel their own paths, but occasionally they line up almost exactly opposite each other in the sky and when this happens you also happen to get a Lunar Eclipse. Now the geometry of this alignment means that the Earth must be exactly between the Sun and the Moon, so it’s fairly obvious that what we’re seeing is the Earth’s shadow covering up the Moon. This much was pretty well-known even in ancient times, but the important detail noticed by ancient astronomers was that the shape of the shadow as it crosses the moon was always round. Now you could try to explain this by saying that the Earth is shaped like a disk, but no matter what angle the Sun-Moon line passes through Earth, the shadow was always the same shape. To a student of geometry (and the Greeks knew all about geometry) there was only one possible explanation: The Earth must be spherical. This posed all sorts of problems, like how come people don’t fall off the sides and the bottom, and led to a bunch of clever-but-wrong theories until Isaac Newton saved the day with his Theory of Universal Gravitation.

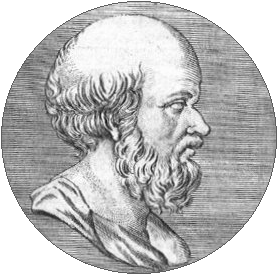

The city of Syene (modern-day Aswan, in Egypt) happens to lie almost exactly on the Tropic of Cancer meaning that at noon on the day of the June Solstice, the Sun shines exactly overhead. If a citizen of Syene were to plant a perfectly vertical stick in the ground at that time, it would cast no shadow whatsoever. When Eratosthenes heard about this trick he was intrigued, as it did not work in Alexandria – there would always be a shadow, no matter what time or date he tried. Since he already knew the Earth to be spherical, it was obvious to him that the Sun’s light must strike Syene at a different angle to Alexandria. It occurred to him that if he knew this angle (Very simple to calculate by measuring the length of the shadow and applying basic trigonometry), and the distance between the two cities, then it would be quite simple to calculate the circumference of the Earth. He did this, and found a figure of 250,000 stadia. Unfortunately nobody is entirely sure how accurate he was, since the stadium was not a standard length – depending on which sources you consult, it is somewhere between 155 and 170 meters. Still, even with this large margin of error, his results were within a few percent of the true figure and remained the most accurate available for a very long time.

The city of Syene (modern-day Aswan, in Egypt) happens to lie almost exactly on the Tropic of Cancer meaning that at noon on the day of the June Solstice, the Sun shines exactly overhead. If a citizen of Syene were to plant a perfectly vertical stick in the ground at that time, it would cast no shadow whatsoever. When Eratosthenes heard about this trick he was intrigued, as it did not work in Alexandria – there would always be a shadow, no matter what time or date he tried. Since he already knew the Earth to be spherical, it was obvious to him that the Sun’s light must strike Syene at a different angle to Alexandria. It occurred to him that if he knew this angle (Very simple to calculate by measuring the length of the shadow and applying basic trigonometry), and the distance between the two cities, then it would be quite simple to calculate the circumference of the Earth. He did this, and found a figure of 250,000 stadia. Unfortunately nobody is entirely sure how accurate he was, since the stadium was not a standard length – depending on which sources you consult, it is somewhere between 155 and 170 meters. Still, even with this large margin of error, his results were within a few percent of the true figure and remained the most accurate available for a very long time.