Wandering Worlds

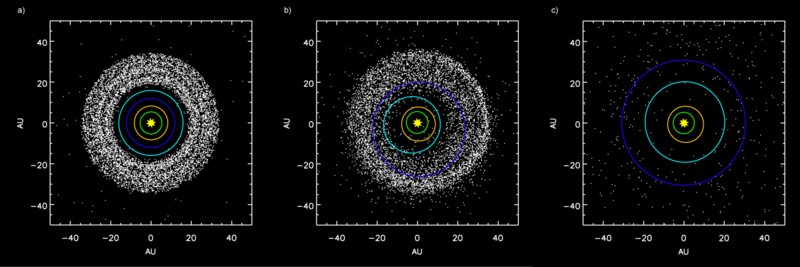

Imagine the scene: A planet, cold and dark, drifting through deep space, attached to no star. Although such a world makes a great science fiction setting, it was long considered a rare, unlikely event. A few years back, however, a team of four astronomers presented a new theory on Solar System formation called the Nice Model – named for the French city of Nice, where the model was developed. This model, which has become widely accepted by astronomers, states that the planets of the Solar System formed in very different locations to where they are now, and that the gravitational influences of the gas giants accumulated over hundreds of millions of years to rearrange things. The planets shifted around, had their orbits manipulated, leaving them in their current positions. One obvious implication of this model is that, while some planets were flung inwards to much closer orbits than they originally possessed, others could have been ejected from the Solar System entirely. The Nice Model makes it entirely possible, or even likely, that there could be many planets drifting through space, frozen to almost absolute zero, orphaned from their long lost parent star.

A few days ago, another, larger, international team of scientists have just released a paper showing the results of their attempt to find out just how common these free planets really are. Their conclusion is astounding: They calculate that our galaxy has approximately two free planets per star – that adds up to hundreds of billions of free planets, wandering between the stars!

The team used a very sensitive technique to analyse data from the 1.8 meter telescope at Mount John University Observatory in New Zealand for signs of ‘microlensing’ – a special case of gravitational lensing. Einstein’s theory of relativity predicted, amongst many other things, that light should be deflected from it’s course by gravity, and this has been confirmed by distortions in images of extremely distant galaxies caused by fainter massive galaxies that happen to lie directly in our line of sight. Microlensing is the exact same process, but on a smaller scale. The specific methods used by the team were capable of detecting objects from the size of Saturn upwards. After meticulously scanning a small region of the sky that is densely populated with stars, they managed to confirm the presence of ten planets not orbiting a planet, that were approximately the size of Jupiter (or larger), and that happened to pass through the exact spot necessary to cause microlensing. A pretty astonishing piece of work, which has allowed some pretty astounding conclusions to be reached!